Robert Lincoln's Military Service

An illustration of how political norms changed between the Civil War and WWI

This piece follows up on something mentioned in my last one, which was the claim that upon graduation from Harvard in June 1864, Robert Lincoln entered Harvard Law School, “yielding most unwillingly to the importunate advice and pleading solicitation of his father.”

That’s quite an interesting description—one that suggests Lincoln’s behaivor bordered on inappropriate. It sounds out of character for Lincoln to be so overbearing and anxious. As Busbey explained, in 1864, “the country was then in the throes of a fierce Presidential contest, superimposed upon the mighty struggle with rebellion.” Then he got to the real issue: Robert had been “kept” at college “sorely against his will”—obviously referring to the fact that Robert had not served in the army since the war had broken out in 1861, something many other Harvard students had left to do. Busbey indicates this was entirely Lincoln’s doing—”Every murmur of defeat…had come to [Robert’s] ears as a voice of reproach, and only the father's constant entreaty had kept him from the field of battle.”

He endured only a few weeks of law school (I believe it was one semester, which coincided with the final months of the presidential campaign in which Lincoln won re-election), Busbey said, out of “filial reverence and the duty which he owed to that father who was the nation's head.” Soon after, he “was assigned to duty upon the staff of General Grant as captain and aide-de-camp.”

Clearly, Busbey was eager to get ahead of questions about Robert’s delayed military service, and had no qualms about pinning it all on Lincoln’s “pleading solicitation,” which he did not fully explain. One gets the impression that he was concerned about Robert’s safety, perhaps not only in the field but anywhere away from the safe, familiar Boston during the vicious re-election caampaign. It’s impossible to know where Busbey got this impression, which he seems to have found touching, but it is generally consistent with what Robert himself wrote in a 1915 letter.

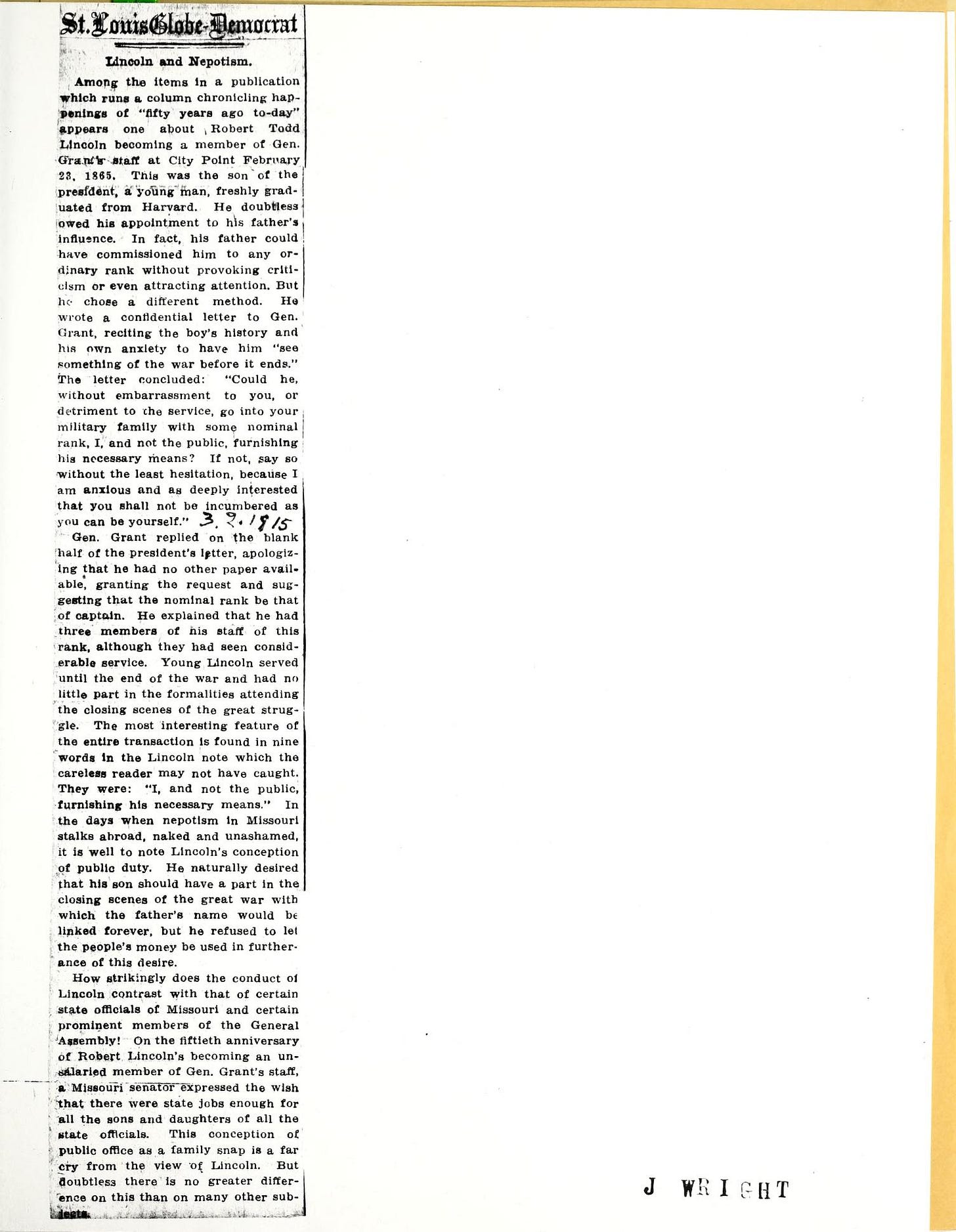

The likely reason he wrote the letter was in response to newspaper articles that surfaced that year. For example, the following St. Louis Globe-Democrat editorial:

The Globe-Democrat had been edited in the 1870s and 1880s by Robert’s close friend, and tended to give him sympathetic coverage despite its affiliation with the Democratic Party (this was the era of the partisan press). It’s not clear whether that dynamic was still in play in 1915, and the column got cut off, but it’s clear that the “nepotism” complaint was not aimed at the Lincolns.

Just over a decade later, in 1926, the matter-of-fact and approving attitude displayed in that editorial was incomprehensible:

The opposition to “influence-peddling” and “nepotism” had been gaining ground in many circles since the 1870s, but World War I had entirely changed expectations as to what was considered acceptable in such cases. Or at least that was the message that the media, which had essentially reached the status of “mass media” during WWI, was sending by 1926.

That Americans’ “political and individual consciences” had “reached a higher plane” than was ever reached by Abraham Lincoln is a bit dubious, and the suggestion that “the boy’s mother” was to blame (see below), was pure speculation. It’s hardly implausible that a mother was distraught at the thought of sending her son off to war. But surely fathers were not strangers to those feelings, even if they were less likely to express them.

By 1933, even publications devoted to Lincoln were struggling to process how he could have could have made such a decision:

“There has appeared at intervals in Lincoln Lore, monographs discussing current criticisms of Lincoln and his policies. No charge preferred against the President seems to have been so well supported as the allegation that ‘He kept his son out of the war for many months while other men's sons were giving their lives for the country.’ This attitude is so contradictory to Lincoln's very nature that one wonders just what did delay the military service of Lincoln's oldest boy.”

(All emphases added.) Dr. Louis A. Warren, who edited Lincoln Lore, went on to say:

“Emilie Todd Helm, widow of the Confederate general, Ben Hardin Helm, spent about one week in the White House in the fall of 1863 and kept a diary which is invaluable. The editor of Lincoln Lore had the pleasure of knowing Mrs. Helm and feels the notes she made at the time of her visit to her sister, Mrs. Lincoln, can be accepted as absolutely reliable.”

As I have mentioned before, Helm was an extremely unreliable source of information. That is almost certainly the case here, but her contributions to books, articles, and interviews from the 1890s to the 1920s, firmly established the idea that Mary Lincoln was to blame.

“This excerpt from the diary of Emilie Helm made at the White House in November, 1863, reveals that he had been appealing to his parents to allow him to enlist:

‘She (Mrs. Lincoln) is frightened about Robert going into the army. She said today to Brother Lincoln (I was reading in another part of the room but could not help overhearing the conversation) : "Of course, Mr. Lincoln, I know that Robert's plea to go into the army is manly and noble and I want him to go, but oh ! I am so frightened he may never come back to us!’”

The heavy-handedness is typical of Helm’s “diary entries” as published in her daughter’s 1928 biography of Mary. Such convenient quotes were pretty obviously not from an actual diary, and Warren included another, even more implausible entry:

“While Mrs. Helm was visiting in the White House General Sickles and Senator Harris called. After they had made some remarks to the widow of the Confederate general about northern victories and had received from her a reply that angered them, according to Mrs. Helm's diary, “Senator Harris turned to Mrs. Lincoln abruptly and said: 'Why isn't Robert in the army? He is old enough and strong enough to serve his country. He should have gone to the front some time ago.' Sister Mary's face turned white as death and I saw that she was making a desperate effort at self-control. She bit her lip, but answered quietly, 'Robert is making his preparations now to enter the Army, Senator Harris; he is not a shirker as you seem to imply for he has been anxious to go for a long time. If fault there be, it is mine, I have insisted that he should stay in college a little longer as I think an educated man can serve his country with more intelligent purpose than an ignoramus.'“

Historians often take this convenient confession of fault at face value, but the sudden belligerence of Harris and Sickles towards two unrelated women dressed in mourning clothes has always seemed implausible to me. Sure, Sickles was unpredictable, and as the widow of a Confederate General, Helm’s presence in the White House may have brought out strong emotions. But Mary was the President’s wife, and both were personally quite friendly with her and the whole Lincoln family even after this incident. I find it unlikely that they suddenly attacked their hostess over Robert’s absence from the military, especially given that the practice of buying substitutes was accepted at the time. It was likely known to them that he wanted to join as soon as was deemed practicable.

Warren concluded by noting that Mary Lincoln’s struggles with mental illness meant she “should [not] be too severely criticised in the attitude she may have taken about her son's enlistment,” as though this were the only possible explanation for the normal motherly feelings portrayed in Helm’s book!

While most sources attribute at least some of the blame to Mary’s fears of losing another child for the delay, having scrutinized the record, I’m not sure what her exact feelings were or how much influence she had on the matter. I have no doubt that she constantly worried about losing her children, but there are hints that her Scots-Irish values could “override” this fear in certain situations. She did not marry or raise cowards, or men who in any way neglected their patriotic duties; nor did she encourage any such dishonorable behavior. Any insinuation to the contrary was an insult, totally at odds with her self-image.

Even after her worst fears came true, as they did with Lincoln’s assassination, she never expressed the wish that he had never become president. And in 1880, when she “escaped” Springfield to seek medical treatment New York City (the saga will be detailed in an upcoming book), one of her first remarks to a journalist was the following:

“Mrs. Lincoln has been very much wronged by the mistaken impression that has gained credence to the effect that she wished her son, the Secretary of War, to resign his office, for fear that some harm would come to him, as there did to his martyred father. She declared that she would not have him desert his spot from any cowardly motives.”

I rest my case for her general attitude on that remark, as it was made within weeks of President Garfield succumbing to injuries inflicted by an assassin. The shooting had occurred in close proximity to Robert, who had been serving Garfield’s Secretary of War, leading to the “mistaken” rumors. The assassination surely stirred up bad memories, but she actually protested that she was “very much wronged” by the claim that she wanted Robert to leave public life! This attitude seems to have become rare by 1880, making it easier to assume that Mary would have been motivated only by her fears.

But the whole matter seems to have been cleared up in 1956 by Dr. Louis A. Warren, who was still editing Lincoln Lore. Historians often repeat the old narrative, but Robert’s words seem clear and dispositive. It seems that Warren had been collecting new information on the matter since the 1930s, and here is his updated assessment:

“When one hears of an individual apparently acting ‘out of character’ it is always important to discover first of all if the reported statements of his behavior are correct and if so, whether or not the motives which are reported to have prompted the unusual procedure have been carefully scrutinized.

Jim Bishop in his recent book ‘The Day Lincoln Was Shot’ ignores the time element with which he is dealing in the second chapter designated as ‘8 a.m.’ to go back and pick up an incident which occurred several months before relating to the Lincoln family's attitude towards Robert, the oldest son, joining the army. Bishop states that after the family had discussed the matter, Mr. Lincoln did something that ‘for him, was mean. (He asked General Grant to give the boy a commission and place him on his personal staff.’ Bishop then goes on to conclude that the inference was that the President ‘did not want his son to be in danger.’

Although the President has been severely criticized by many authors who have felt he was somewhat "out of character" in this procedure it has not heretofore been affirmed that he was "mean" about it.

Robert Lincoln entered Harvard College in the fall of 1860 and was still a freshman, eighteen years of age, when the first call for volunteers was made in April 1861. The great numbers of men who enlisted during the summer seemed to fill the ranks and Robert started in his sophomore year in the fall. Early in the spring, however, he apparently got the war fever and acquired a book entitled Cadet Life at West Point in which he wrote on the flyleaf ‘R. T. Lincoln, Harvard College, March 1862.’ The back of the front cover of the book now in the Foundation library bears a book plate of Robert's father-in-law, W. A. Harlan. A month before Robert had acquired this book his brother, William, died in the White House. The mental anguish of his parents at this time would cut short any enlistment plans and he finished his sophomore year while yet in his teens.

The junior year at Harvard began before the draft act was confirmed, but now with its passing Robert had a new argument to warrant his enlistment. Apparently, however, the suggestion that he should finish college took root about this time and he returned to college as a senior in the fall of 1863. Apparently Robert was getting insistent about entering the army, but his mother had not been willing to acquiesce. Emily Todd Helm recorded in her diary while in the White House in November 1863 that Mary was frightened about Robert enlisting. Emily recorded this conversation between Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln:

’Of course Mr. Lincoln I know that Robert's plea to go into the Army is manly and noble and I want him to go, but oh! I am so frightened that he may never come back to us.’ Mrs. Helm then states Lincoln replied, ‘Many a poor mother, Mary has had to make this sacrifice and has given up every son she had — and lost them all.’[Note: I find this exchange implausible, as there are accounts of Lincoln allowing for the discharge of soldiers following the death of a male relative, whether it occurred in the line of duty or not, on the grounds that their family could not survive another loss. He does not seem to have believed that a mother should be prepared to sacrifice all her sons, and Helm’s credibility issues only strengthen my skepticism.--KE]

Robert Lincoln's entry into the army at any time in 1864 with the Union party convention on June 7 and the election of December 8 coming up would have been unwise. While Robert may have been a "political liability" out of the army, the President would have no part in an enlistment which would be construed by his opponents as a political maneuver to gain votes. This situation may have been party responsible for Robert remaining to graduate.[Note: I suspect Robert’s enlistment would have helped Lincoln politically more than it hurt him, and I doubt Lincoln would have been particularly sensitive to such sniping. It is possible, however, that Lincoln was worried it would lead people to question Robert’s motives in the future, and wished to minimize Robert’s prominence in the vicious 1864 campaign by keeping him quietly in Boston.—KE]

At this point we may pick up the story from a letter written by Robert Lincoln on March 2nd, 1915 to Winfield M. Thompson. Referring to his father, Robert wrote:‘At the end of the vacation after my graduation from Harvard, I said to him that as he did not wish me to go into the army (his reason having been that something might happen to me that would cause him more official embarrassment than could be offset by any possible value of my military service), I was going back to Cambridge to enter Law School. He said he thought I was right.’

Robert entered Harvard Law School on September 5, 1864. The election was over on November 8 and when Robert came home in January 1865 the old question of entering the army came up again. In another paragraph in the letter to Thompson, Robert wrote, still referring to his father: "His letter afterwards to General Grant was the result of my renewed appeal to him."

In this letter to Grant dated January 19, 1865 making known Robert's wish to enter the army the President wrote: "I do not wish to put him in the ranks, nor yet to give him a commission . . . could he without embarrassment to you or detriment to the service go into your Military family with nominal rank, I and not the public furnishing his necessary means." Both the salutation and conclusion of the letter were in apologetic terms and left the matter entirely to Gen. Grant. Grant replied on January 21: "I will be most happy to have him in my Military family in the manner you propose. The nominal rank given is immaterial, but I would suggest that of Capt."

The most important part of Robert Lincoln's letter to Winfield M. Thompson is the sentence within the brackets which were placed there by Robert himself. The statement sets forth the primary reason why the oldest son of the President did not enter the army until near its close and even then was kept from the ranks. Robert clearly states, and he should know the facts, that his failure to enter the army was primarily due to his father's fear of ‘official embarrassment’ which might accrue from Robert's entering the military service.

It is not difficult to visualize several situations in which Robert might have become involved, either through natural procedures or premeditated situations purposely created by Lincoln's enemies. He wrote on one occasion, "But I have bad men also to deal with, both north and south. ... I intend keeping my eye on these gentlemen, and to not unnecessarily put any weapons in their hands."

[Note: It’s hard to imagine a worse situation than Robert being taken hostage by Confederate sympathizers who hoped to extract concessions from Lincoln.--KE]

The plans which had been made by corrupt politicians to strike at the President by attempting to compromise his wife would not be soon forgotten and he did not intend to make his son available for ulterior purposes. Even after Robert had been allowed to join the army and was proceeding to his appointment Lincoln apparently became worried and observed in a telegram to Grant: ‘I have not heard of my son's reaching you.’ Grant replied immediately and assured the President that his son had arrived.

Mr. Lincoln has been accused of shielding his son from dangers prevalent to warfare, bowing to the pleadings of his mentally ill wife, or relieving himself from sorrow should his son become a casualty. The President's dread of interference with his official duties or contemplated embarrassment to the administration was the fundamental consideration. The great task in which he was engaged, superseded any selfish purpose in his attitude towards his son's enlistment.

Abraham Lincoln may not have been ‘out of character’ after all in this much discussed episode. Certainly he was not "mean" in his request to General Grant and very conscientious about not allowing barriers to obstruct his own task as President of the nation and as commander-in-chief of the armies of the republic.

So, there we have it. Lincoln was indeed a concerned father, and he saw how those concerns could be weaponized against him to the detriment of the country.

Off topic (by over half a century), but as I was researching the famous meeting in London between Thomas Jefferson/John Adams and the Muslim ambassador from Tripolitania (now Libya) in 1786 to discuss the problem of piracy. During the approximately 90 minutes I was at the library thumbing through one volume after another from two multi-volume sets of Jefferson papers, I stumbled across a related letter from John Adams in which he had met with that same Muslim ambassador in London at a date prior to the more famous meeting with Jefferson also present. At that prior meeting, Adams describes how the ambassador insisted that Adams sit on the floor and smoke tobacco from a giant houkka (water pipe) and also to drink very strong coffee. After Adams had taken a couple of puffs off the pipe, he reported that he felt a little sick and that the ambassador's underlings exulted, and said excitedly to Adams "Now you are a Turk!"

P.S. -- I am also the Twitter handle Doctor Doctor, My Real Name is Proctor @ArguiteAdVodkam