Missed Opportunities in Lincoln Gossip, Pt. II

Will we ever know the truth about the Lincolns' courtship?

Continued from Part I.

D. W. Craig

One of Simeon Francis’s Springfield employees, D. W. Craig, who knew Lincoln and many of his close associates, also ended up in Oregon.1 Craig died in 1916, after having been involved in practically every newspaper that had ever been published in that state.2 When prominent journalist Fred Lockley had interviewed him in 1913, Craig provided a rare glimpse at the courtship. While his comments have gone entirely overlooked, his intimacy with the Francises meant he had a good opportunity to learn what really happened.3 The piece was not very artfully written, but here is the relevant portion:

“A good deal of their courting . . . was done at the home of Mrs. Francis. One night Mary Todd came into the room where Mrs. Francis was and threw herself on the couch and began sobbing as though her heart were broken. Mrs. Francis said, 'What is the matter, Mary?’ Mary said, ‘Mr. Lincoln has left and I know he will never come back. Call him back, call him back.’ Mrs. Francis went to the front door. Lincoln was just closing the front gate. ‘Don't go, Mr. Lincoln,’ she said. ‘Mary wants you to come back.’ Lincoln latched the gate and said, ‘No, I will not come back.’ ‘I think you ought to come back,’ Mrs. Francis said. ‘Mary is crying and feeling so badly that you can at least come back and let her explain matters if you have had a misunderstanding.’ Lincoln paused a moment and finally said, ‘Very well, I will do so,’ and came back and they had soon fixed up their lovers[‘] quarrel.”

To say the least, readers could have used more context! Lockley apparently wasn’t familiar with how every piece of their courtship had been dissected by biographers for decades. So, he didn’t ask what caused the quarrel, or why Lincoln caved so quickly, or what Mary explained, or how they reconciled. Though Craig knew Herndon and must have been familiar with the controversy, he didn’t undertake to resolve it. All we can take from it is that Craig heard about resistance on Lincoln’s part even after the couple reunited at the Francis home, though he didn’t indicate that any breakup had ever occurred. From the lack of detail and Mrs. Francis’s response, he seems to have viewed it as routine romantic drama that was easily patched up.

Ella Rhoads Higginson

One of the young journalists both Craig and Lockley interacted with was Ella Rhoads Higginson, later a noted poet in Washington State. This brings us to another bizarrely neglected lead, one I stumbled across on worldcat.org.4 In early 1896, she wrote to Samuel S. McClure, editor of McClure’s Magazine. Its most recent issue had featured fiction by Higginson, as well as the beginning of a 20-part series on Lincoln by Ida Tarbell, who would go on to make quite a name for herself as a journalist. In the letters, Higginson thanked McClure for publishing "so many of my stories last year," but her concluding paragraph was the most interesting:

"By the way, would an original poem by Lincoln, published in a paper during the period of his broken engagement with Mary Todd, anecdotes of their courtship, including the exact words with which she finally renewed the engagement, be of any value to you?"5

I can’t imagine that McClure’s answer to that question was no. But her scoop was never published, and no reply or further mention exists. McClure and Tarbell seemed to be going for a rather wholesome Lincoln—light on suicidal inclinations, melodramatic anonymous poetry, romantic drama, and Mary Lincoln generally.

That is, if McClure even believed her offer was sincere or credible to begin with. This claim would be totally implausible if made by most people, and was easily fabricated from details in the 1872 biography, which included quotes from Lincoln’s best friend, Joshua Speed, about the aftermath of the breakup. Here’s the relevant passage, written decades after the events and in an exaggerated manner:

“’We had to remove razors from [Lincoln’s] room,’ says Speed, ‘take away all knives, and other dangerous things. It was terrible.’… [Speed] took Mr. Lincoln with him to his [family’s] home in Kentucky, and kept him there during most of the summer and fall, or until he seemed sufficiently restored to be given his liberty again at Springfield, when he was brought back to his old quarters. During this period, ‘he was at times very melancholy,’ and, by his own admission, ‘almost contemplated self-destruction.’ It was about this time that he wrote some gloomy lines under the head of ‘Suicide,’ which were published in ‘The [Daily Illinois State] Journal.’ Mr. Herndon remembered something about them; but, when he went to look for them in the office-file of the ‘Journal,’ he found them neatly cut out, — ‘supposed to have been done,’ says he, ‘by Lincoln.’”6

But Higginson’s connections with the Portland newspaper community make a difference—it is plausible she really did know the true story. Perhaps she had the context that Craig had neglected to give, whether from him or the Francises, who had extended family in Whatcom County, WA, where Higginson spent most her life.7 When it came to poetry by Lincoln published “in a paper,” as well as the details of his quiet second courtship, the Francises were the best possible source. Certainly, the alleged verbatim conversation could only have come from a few people—Higginson must have been claiming insider knowledge.

Higginson did not mention that the topic was "suicide,” but seemed to imply that it was connected to the breakup. It’s possible that Lincoln, who liked to write poetry, submitted more than one anonymous piece during that period of personal misery. Notably, she appeared to know the full text of the poem, perhaps even to have seen the original newspaper clipping, which Herndon had searched for in vain. Again, this points to knowledge the Francises would have possessed. In fact, in 1938, Allen Francis Edgar revealed that he possessed Simeon’s scrapbook, which included copies of poems published in the Journal. Edgar was a great-grandson of Simeon’s brother Allen, whose family had lived in the same part of Washington State as Higginson!8

Though she lived until 1893 and seems to have gossiped with Oregonians, Mrs. Simeon Francis refused to answer Herndon’s inquiries about the matter, writing “my intimacy with Mr & Mrs Lincoln was of so sacred a nature, that on no consideration could I be induced to open to the public gaze, that which has been buried these many years. To me it would look like a breach of trust.”9(Simeon’s sister-in-law reportedly told her grandson that “Mary Todd…met her equal when she met Mrs. Simeon Francis,” whatever that means!)10

In the years after Higginson wrote these letters, McClure’s would become known for its "Lincoln Bureau." In 1898, the magazine published a piece by Mary’s half-sister, Emily Todd Helm, which denied Herndon’s claim that there were two wedding ceremonies, and that Lincoln had failed to show up for the first one.11 In later works about Lincoln, Tarbell concluded that this story was a total fabrication, but while she corresponded with Allen Francis Edgar, she is not known to have talked to Higginson about this.

I reached out to Dr. Laura Laffrado, of Western Washington University, who studies Higginson. She determined that the letter is part of a mostly uncatalogued private collection donated to the University of Virginia, and told me that Higginson had a weekly column for four years in the Seattle Times. In it, Higginson mentioned many names, but nothing about the Lincolns. Perhaps more manuscripts will surface and shed light on the matter, but Higginson burned most of her correspondence. So far, S. S. McClure’s papers have turned up no reply or further mention, but the survival of the letters would seem to indicate they were probably not carelessly tossed aside. (They have a strange pencil mark on them that might have indicated they were rescued from a rejection pile.)

Hervey W. Fowler

Finally, there is the case of Hervey Fowler. He was a west coaster, but not an Oregonian. A native of Illinois, he spent his later years in Santa Cruz, California. As a young man, he had met Mary Lincoln when she moved to his mother’s Chicago neighborhood in 1865. The friendship between Mary and the Fowler family is well-documented.12

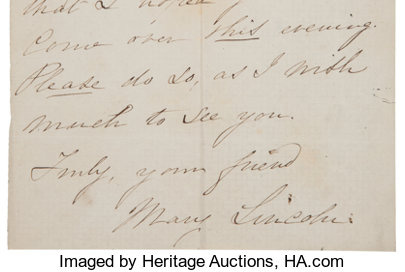

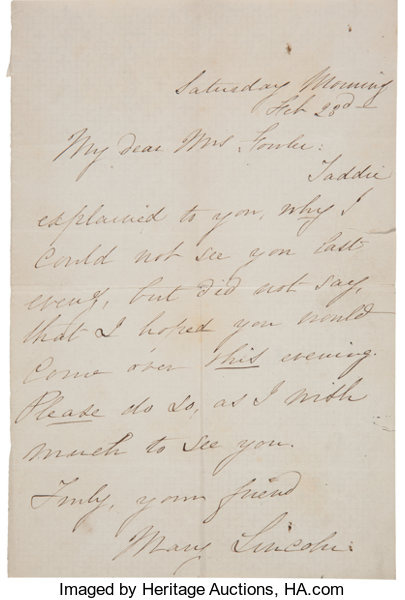

The above is a letter from Mary to Hervey’s mother, from 1867.

My dear Mrs. Fowler:

Taddie explained to you why I could not see you last night, but did not say that I hoped you would come over this evening. Please do so, as I wish much to see you.

Truly, your friend,

Mary Lincoln

As the centennial craze started in 1909, he was prompted to write a letter to the editor of a local newspaper, in which he recounted an experience that can only stir envy in Lincoln scholars. What follows is a short excerpt, lengthened by the fact that Fowler had a penchant for maximizing adjectives.

“[A] law partner of Mr. Lincoln [Herndon], published in a prominent Chicago daily paper a romance . . . These articles, embellished by the most sensational and florid language, described the anguish and hopeless sorrow of Mr. Lincoln on the death of his ‘first and only love,’ (Ann Rutledge of New Salem), and stated that while he had the highest respect and affectionate regard for the woman who he later chose to be his wife, and to whom he was loyally devoted throughout his life, still, he had no deep or heartfelt love for her . . .

The insidious and delicate nature of the affront was such that no public notice or denial could be take nor made; and so . . . [Mrs. Lincoln] suffered this deepest possible hurt to a sensitive woman’s heart without public utterance or refutation. In indignation at the injustice done the sacred memory of her illustrious husband, she sought, with all the intensity of her ardent nature, to demonstrate to her closer friends the bas[e] falsity of any charge of perfidy or duplicity attributed to her husband; and with this in view I recall with distinctness her bringing to my mother for perusal, a package of several letters written to her by Mr. Lincoln; a few before, and many of them after their marriage. With Mrs. Lincoln’s permission, my mother gave me three of these letters, which I carefully read. if I ever read or heard genuine love letters these were such. I specially recall one of them written by Mr. Lincoln late at night, at the headquarters of General Grant; the day before Richmond was entered by the army of the Potomac. Notwithstanding the lateness of the hour and the burden of great responsibility that especially at that moment rested upon him, his letter fairly pulsated with expressions of them most tender and devoted love. No mere lover does, nor can, so pour out his very heart in language of loyal and sympathetic affection. It portrayed in most beautiful directness and mirror-like detail, the soul of the tender, shielding husband, the devoted thoughtful father, the brave soldier, the hopeful patriot, and lastly the great, playful boy. I would that letter, with a recital of the circumstances that occasioned its writing, could be in every reader of every public school in this broad land.”13

The last known handwritten message from Lincoln to his wife is dated April 2, 1865, which was the day before Richmond was entered by Union troops. Lincoln was at Grant’s headquarters at City Point, and it is thought to have been telegraphed to her in Washington, where she had returned the day before, though no telegraph markings appear on it. The provenance is unclear, and almost none of Lincoln’s letters to his wife survive. But it seems possible that the letter was delivered by courier and preserved by Mary Lincoln, and somehow found its way to the Gilder Lehrman Collection.14 If so, this could have been what Fowler saw. But, even with the dramatic flair he displays in his writing, it is hard to see how he could have read pulsating romance into this letter:

“Mrs A. Lincoln,

Washington, D.C.

Last night Gen. Grant telegraphed that Sheridan with his Cavalry and the 5th Corps have captured three brigades of Infantry, a train of wagons, and several batteries, prisoners amounting to several thousands– This morning Gen. Grant having ordered an attack along the whole line telegraphs as follows

‘Both Wright and Parks got through the enemies lines– The battle now rages furiously. Sheridan with his Cavalry, the 5th Corps, & Miles Division of the 2nd Corps, which was sent to him since 1. this A.M. is now sweeping down from the West. All now looks highly favorable. Ord is engaged, but I have not yet heard the result on his front’

Robert [Lincoln, their son, who was serving on Grant’s staff] yesterday wrote a little chearful [sic] note to Capt. Penrose, which is all I have heard of him since you left. Copy to Secretary of War

A Lincoln”

A love letter that ends with “Copy to Secretary of War”?!? And the rest of it is a dry, factual account. Even the remark about their son Robert reveals nothing tender in the least. Was he simply imagining it all, or confusing it with another of the letters he saw? Or did he see another, more personal letter written that day, a follow-up to the short telegraphic update?

This seems pretty likely, as further research indicates that the “letter” was almost certainly a telegram.15 Mary would not have received the actual handwritten document, only the message it contained.16 At the time it was written, Mary Lincoln had departed City Point for the White House following an emotional meltdown in which she lashed out at her husband and others. One witness recalled that “the mental strain upon her was great, betrayed by extreme nervousness approaching hysteria, causing misapprehensions, extreme sensitiveness as to slights, or want of politeness or consideration.” Lincoln appeared to feel “deep anxiety for her,” and “his manner toward her was always that of the most affectionate solicitude.”17 Mary Lincoln’s mental instability is well-chronicled, and the main trigger was likely the four years of anxiety that burst forth once the war ceased to override all other concerns. While Mary appears to have become reconciled to her husband before she left, this situation would have given Lincoln good reason to mail her a private letter of “loyal and sympathetic affection” in addition to his regular telegraph updates.18

Fowler died a year later, and took whatever else he knew about those letters to the grave. While the Fowler descendants have come forward with many Mary Lincoln relics and letters, we’ll probably never know what he was lucky enough to peruse way back in the 1860s.19

George H. Himes, Letter to the Editor, Oregonian, July 25, 1909. “After serving an apprenticeship…Craig…went to … Springfield, remaining…four years as an employe[e] of the Illinois State Journal, edited by Simeon Francis, who came to Oregon in 1859, and during the nest two years a was employed on The Oregonian in an editorial capacity in addition to setting type. While employed on the State Journal, Mr. Craig performed the duties of printer, reporter, editorial writer, and telegraph operator.” This 1909 Sunday Oregonian piece—coinciding with the Lincoln Centennial—specifically focused on then-80-year-old Craig’s interesting life: “During his spare hours in Hannibal, Mr. Craig read law, and followed that habit in Springfield, Ill., most of the time in the office of Lincoln and Herndon. In due time he successfully passed a most rigorous examination, his examining committee being B.S. Edwards, John T. Stewart [Stuart] and Abraham Lincoln, and was licensed to practice on September 15, 1850, the license being signed by S. H. Treat, Chief Justice, and Lyman Trumbull, associate. He then practiced law and on occasion … performed editorial work on the Journal until the latter part of 1852.” Every person mentioned here had some connection to the Lincoln wedding, but this was the only mention of Lincoln in the piece!

Ibid. A detailed history of his varied career is given. “He was able to fill every position in connection with the publication of a newspaper from editor to office boy, with credit to all concerned.” It was noted he still frequently contributed to the local press, and that “His range of information regarding the history of the world is surprisingly large, and in addition he reads and writes in Latin, Greek, Hebrew, French and Spanish.”

The Oregon Daily Journal, September 30, 1913.

The description reads: “Higginson writes to thank McClure, 1896 Jan 7, for the illustrations of her ‘1900 Woman’ in The Oregonian as well as his kindness in accepting so many of her stories last year. She concludes by asking whether ‘an original poem by Lincoln, published in a paper during the period of his broken engagement with Mary Todd, anecdotes of their courtship, including the exact words with which she finally renewed the engagement’ would be of any interest to him. Attached is an undated, unidentified print of a biographical sketch and photograph of Ella Higginson. In letters Oct 19 and Nov 23, no year, Higginson returns a proof and asks McClure to notify her of publication. She also asks about his use or return of her ‘Knucklin' Down’ stories and asks whether he would have any objections to the republication of her stories in a book.” “Ella Higginson letters to S.S. McClure, 1896, no date,” Clifton Waller Barrett Library (University of Virginia Libraries), https://www.worldcat.org/title/ella-higginson-letters-to-ss-mcclure-1896-no-date/oclc/420531318.

Ibid.; Ella Higginson Letters, 1896, no date, in the Clifton Waller Barrett Library, Accession #14719, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

Lamon, The Life of Abraham Lincoln. Herndon’s notes show he was uncertain about the date of publication, noting it could have been published as early as 1838, though the breakup occurred in late 1840 or early 1841. Speed himself seems to have been confused about the timeline after so many years. For more details, including about the alleged discovery of the poem in an 1838 issue of the Journal, see Joshua Wolf Shenk, “The Suicide Poem,” The New Yorker, June 7, 2004, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2004/06/14/the-suicide-poem.

On January 25, 1904, Whatcom author and historian Charlotte "Lottie" T. Roeder published a piece called “Christmas on Bellingham Bay in the Early Seventies” in the Bellingham Herald. She recalled visiting Mrs. Hofercamp, a niece of Simeon Francis, in the 1870s. Roeder was only a young girl at that time, and her memories must have been fuzzy by the time she wrote the article. She said Hofercamp had told her, “I have my mother’s black dress, worn at the party in father’s house in Illinois, where Mary Todd agreed to become Mrs. Lincoln,” she could have been talking about her aunt, Simeon’s wife, who had no children and would have given any such items to her nieces. Roeder’s mother, more curious than the journalists of the region, asked for more details. Hofercamp’s response was allegedly “There is not much to tell--only [that] Mary Todd had been giving Abraham Lincoln some little trouble by evading his proposals,” which is an interesting twist on the classic story. Roeder remembered that this was followed by a joke: “at this party he agreed to slavery… He agreed to become a slave to matrimony.’” The accuracy of this recollection is dubious, but Roeder did know Cecilia Francis Hofercamp, daughter of Simeon’s brother Allen Francis. And, consistent with Roeder’s recollection, Allen’s children repeatedly claimed that it was at their home that Lincoln was either introduced or became engaged to Mary Todd, which the record does not support. It is true that Lincoln was also very friendly with Allen Francis when he lived in Springfield, and probably visited often.

Daily Illinois State Journal, February 12, 1938. Speaking of missed opportunities, Edgar told Tarbell that his mother, a sister of Hofercamp, always wished she had known some author who could have published her Lincoln reminiscences! Higginson probably also knew Francis Fisher Browne, a journalist and Lincoln biographer who moved from Chicago to the west coast. As luck would have it, his death in 1913 prevented him from finishing a revised edition of the biography, which contained many details of the courtship. Oregonian, May 12, 1913.

“Eliza Rumsey Francis (1793-1893).” Mr. Lincoln and Friends (blog). Accessed September 30, 2020. http://www.mrlincolnandfriends.org/the-women/eliza-francis/.

Allen Francis Edgar to Ida M. Tarbell, May 12, 1927, Ida Tarbell Collection, Allegheny College. While Edgar was one of those referred to in n14, who dubiously claimed that Lincoln met Mary Todd at Allen Francis’s house, he said his grandmother, who was Allen’s daughter, confirmed that “Mrs. Simeon Francis was the one who really made the match of Lincoln & Mary Todd.” Yet his grandmother also said that “Mary Todd made Lincoln’s life miserable,” and that Mrs. Simeon Francis, being Mary’s “equal,” “didn’t hesitate to tell [Mary] about her manners and dress.” It is difficult to see why Mrs. Simeon Francis would have put so much effort into the match if she disapproved of Mary, and it seems unlikely that the breakup had much to do with her “manners and dress.”

Emily Todd Helm, "Mary Todd Lincoln," McClure's Magazine (September 1898). For various reasons not detailed here, Helm’s claims should be treated with skepticism. The most significant is that she was a young child when the wedding occurred, and lived in another state, so she had no direct knowledge.

See, for example, “Mary Todd Lincoln: Autograph Letter Signed with Free Frank, Lot #43077,” Heritage Auctions,

Hervey W. Fowler, Letter to the Editor, Santa Cruz Sentinel, December 30, 1908.

Abraham Lincoln to Mary Todd Lincoln, April 2, 1865. (Gilder Lehrman Collection, GLC08090). Lincoln dated it April 2, 7:45, 1865, and it is believed to have been written at 7:45 A.M., rather than at night, as Fowler described.)

A received copy of the message was found in the recently digitized Union Army telegrams from The Thomas T. Eckert Papers at the Huntington Library. See “Message from Lincoln to his Wife,” Decoding the Civil War Talk, October 22, 2016. See also “Autograph Letter Signed (‘A Lincoln’) TO MARY TODD LINCOLN in Washington, D.C.,” Barnebys.com (“[The letter was] probably intended for telegraphic transmission although it bears no markings to that effect… Provenance: Anonymous owner.”)

A City Point official could have given her the draft later, as a sentimental gesture, but she destroyed all of Lincoln’s letters to her, so there’s no explanation for why it would have survived.

John S. Barnes, “With Lincoln from Washington to Richmond in 1865,” Appleton's Magazine, vol. IX. no. 5, May 1907.

Earlier on April 2, Mary had sent a telegram from Washington: “Arrived here safely this morning, found all well―Miss, Taddie & yourself very much―perhaps, may return with a little party on Wednesday―Give me all the news.” Later that month, during a carriage ride, Lincoln told her, “We must both, be more cheerful in the future—between the war & the loss of our darling Willie—we have both, been very miserable.” Justin G. Turner and Linda Levitt Turner, editors, Mary Todd Lincoln: Her Life and Letters (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972.)

Fowler could have invented the letter based on the details of the telegram, which I believe had been published by 1908. But, like everyone else mentioned, he went decades without sharing his well-documented and interesting Lincoln connection, so attention-seeking does not seem to have been a motive.