Shortly before Mary Lincoln left Washington following her husband’s assassination, the following piece was published in the Washington Chronicle:

“The munificent voluntary contribution of Marshal O. Roberts, of New York, to the widow and family of our murdered President, should be emulated by others who, it is supposed, indulged the same earnest sympathy and are equally able to give it practical operation. We must not forget that this families now national property and entitled to national guardianship. Had Abraham Lincoln not been called to the Presidency and compelled by his constitutional obligations to assume the awful responsibilities resulted from an unparalleled rebellion, he would now, in the natural course of things, be living at peace with his wife and children in the little city of Springfield, Illinois, though not so widely known, yet beloved and respected by his friends and neighbors . . . He fell because he had done is whole duty to his country. A vigilant, unawed and conscientious sentinel, he was a sacrifice to the cowardly hate of his country’s foes. It is well to express the sorrow that flows from the popular heart, and it is better to commend the widow and children to the are of Providence. It is appropriate, too, that there should be tributes fashioned for and erected to the memory of the illustrious patriot. But something more is due. The gratitude and affections of a great people l should take immediate shape in precisely such manifestations, the example of which has been so generously set by Mr. Roberts[.]”1

Mary made no effort to hide this generous gift, and was not ungrateful. During the Old Clothes Scandal, The New York News had a long article, almost certainly at Mary’s urging, that included an interview with Elizabeth Keckly. The article became the outline for Behind the Scenes, which was published shortly afterwards and contained the same information about Roberts.

Keckley spoke of how Mary had been promised $100,000 in private donations, $10,000 each from ten wealthy men. Her letters reveal who these men were intended to be.

“[Only] one gentleman, Mr. Marshall O. Roberts, paid the assessment. By his own hands he forwarded her that amount to Washington. Another gentleman sent her two thousand dollars. This made twelve thousand dollars; all in the way of donations ever received by her, though the Philadelphia Union League promised her $50,000 and other Republican organizations in that city, Washington and here, agreed to give her handsome amounts. When she thinks persons mean well, she endeavors to let them see that she appreciates their kindness, but at the Republican party she feels extremely indignant, for not taking care of her as they ought to have from the relations that she bore to it.”

Her letters show she sent Roberts some relics of her husband in return.

As an illustration of people’s short memories and the speedy loss of significance of such press “scandals,” even by journalists, when Roberts died shortly before Mary turned to America, a blurb circulated widely: “Marshall O. Roberts has left few equals. It is only since his death that the world has heard of the $10,000 cheque that he sent to Mrs. Lincoln after the assassination of her husband, who was too good a man to have accumulated wealth.” Such comments probably contributed to charges against Mary of ingratitude, despite her public acknowledgements at the height of the Old Clothes scandal and its inclusion in Behind the Scenes.

The papers also noted that “This act of genuine benevolence was done quietly through the hands of Colonel Forney.” It had not exactly been done quietly, but who publicized it in 1880 is unclear. Forney, a Democrat himself, had stood by Mary, and being a press man, probably could not resist the story. However, he did not tell all until much later. In his 1880 book The Life and Military Career of Winfield Scott Hancock, which may have brought the matter back to public notice, he went beyond the biography to comment on politics and events generally. He even decided to include a random “Ladies of the White House” chapter:

“Of Mrs. Mary Todd Lincoln, wife of the murdered President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln, I do not allow myself to write at length. Her life was so eventful, and so full of trials, and at the last so saddened by the terrible tragedy of our age, that I cannot lift the curtain to revive the memories of the great civil war . . . One incident I may mention: After his assassination, she remained behind in the White House . . . with her little son . . . ‘Tad," . . . My dear friend, Marshall O. Roberts, of New York, still living, had sent me a check for ten thousand dollars to administer to her immediate wants, as a genuine evidence of his kind and thoughtful nature. She was in her bed-room when I asked to be admitted, to hand her this welcome contribution, and the poor little boy, since called to his home, a curious, quaint child and witty and winning, crawled into my arms and pointed the way to his mother. The double agony, the wild animal-like grief of the elfin child, the deep horror of the stricken mother, with the fresh memory of the murdered father, made up altogether such a scene as can neither be described nor forgotten.”

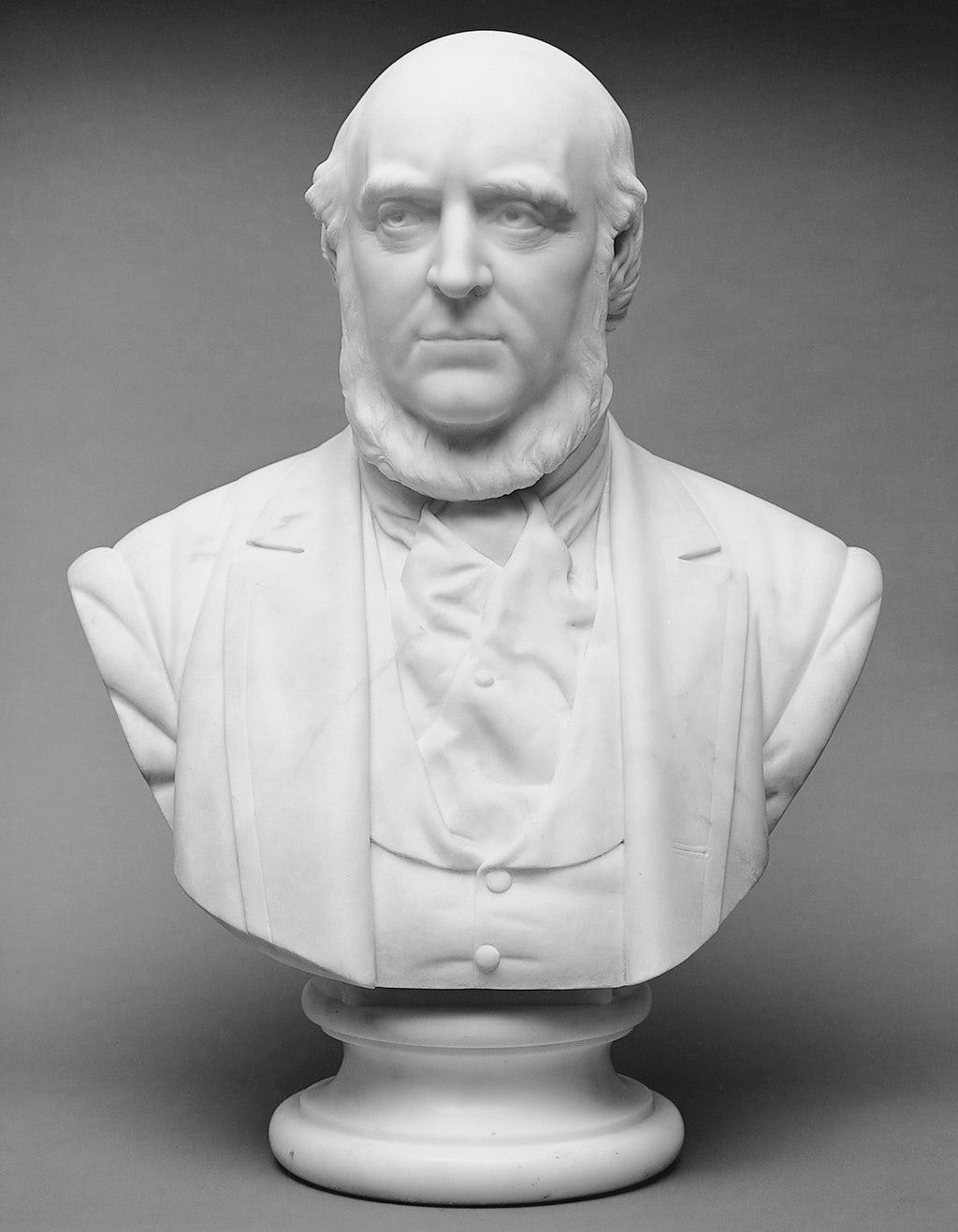

While Mary Lincoln certainly attempted to acknowledge Marshall O. Roberts’ generosity to her in the weeks following her husband’s death, the events of Roberts’ life and his connection to the Lincolns are rarely remarked upon, so I wanted to clarify the record on this point.

From the blog Daytonian in Manhattan by Tim Miller:

In 1833, at the age of 20, Marshall Owen Roberts started in business as a ship chandler at No. 36 West Street. Decades later The New York Times would attribute his astounding success to qualities he received during his "common school education," saying "While a boy at school he was characterized by his strong common sense, his natural shrewdness, his pluck, and his boldness."

In truth, he was greatly aided by two wealthy brothers with whom he became fast friends. Prosper M. and Robert C. Wetmore were prominent in political circles. When President John Tyler took office in 1841, the brothers gave Roberts a contract for naval supplies for the Port of New York.

Roberts steadfastly increased his business, adding cargo ships to his fleet. In 1850 the Government gave him the contract to supply mail service between New York and San Francisco. With the Wetmore brothers and another investor, George Law, he established the United States Steam-ship Company specifically for that purpose. In addition, new steamships transported mail to Havana, New Orleans and Aspinwall in Panama.

When Roberts heard of the attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861, he sent his steamer, the Star of the West, loaded with provisions to Major Robert Anderson and his Union soldiers. He then put his entire fortune into United States bonds to sustain the Government's credit. It was not totally altruistic or patriotic, however. He charged the Government 90 percent interest. The war also provided him with large supply naval supply contracts, and he leased steamers to the Union. The New York Times later noted "During the war his fortune increased ten-fold."But before the first shot of the war was fired Roberts had amassed a fortune large enough to erect a princely home on Fifth Avenue at the southeast corner of 18th Street. The family was listed at No. 107 Fifth Avenue by 1857.

…In 1847 Roberts had married Caroline D. Smith, daughter of and the Hartford merchant Normand Smith, Jr. She was his second wife, and, according to The American Annual Cyclopedia, "was highly educated, and carried to her prominent and exalted position, as the wife of a great merchant, the graces of a well-cultivated and remarkable intellect."

Roberts had two children by his previous marriage, Isaac and Mary. His marriage to Caroline produced another daughter, also named Caroline. While her husband engrossed himself in business, Caroline focused on social work. Her passion for helping the underprivileged caused a newspaper later to say she had a "peculiar saintliness of character."

She was instrumental in organizing the Wilson Industrial School for Girls on Avenue A in the 1850s. An appeal in The New York Times on November 2, 1857 said that the directors hoped that "some, in the enjoyment of comfortable homes and firesides, will remember the little suffering creatures provided for by this Institution."

A member of the Ladies' Christian Union, during the Civil War years she helped found the Young Women's Home on nearby Washington Square; and joined in the efforts of the New-York Ladies Army Aid Association to outfit Union regiments with "havelocks, flannel shirts, jackets, drawers, and socks," as noted in The New York Herald on May 30, 1861. Two weeks earlier, The Times had reported the women had "sent out fourteen boxes of well-prepared articles, both for field and hospital use."

Roberts's massive wealth was evidenced following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. The Times reported that he "sent his personal check for $10,000 to Mrs. Lincoln."

Marshall Roberts was an avid collector of art. His personal art gallery to the rear of the mansion filled with costly works. The New York Times said "This love of art became an absorbing passion. He made no pretensions to connoisseurship, but was guided in his purchases simply by fancy, or with

a view to assisting some needy artist."

Interestingly, there is also some evidence that Roberts tried to hire Mary a lawyer during the dispute over her sanity in 1875-76.

“A Word for Mrs. Lincoln,” Washington Chronicle, reprinted in the Cleveland Leader, May 4, 1865.